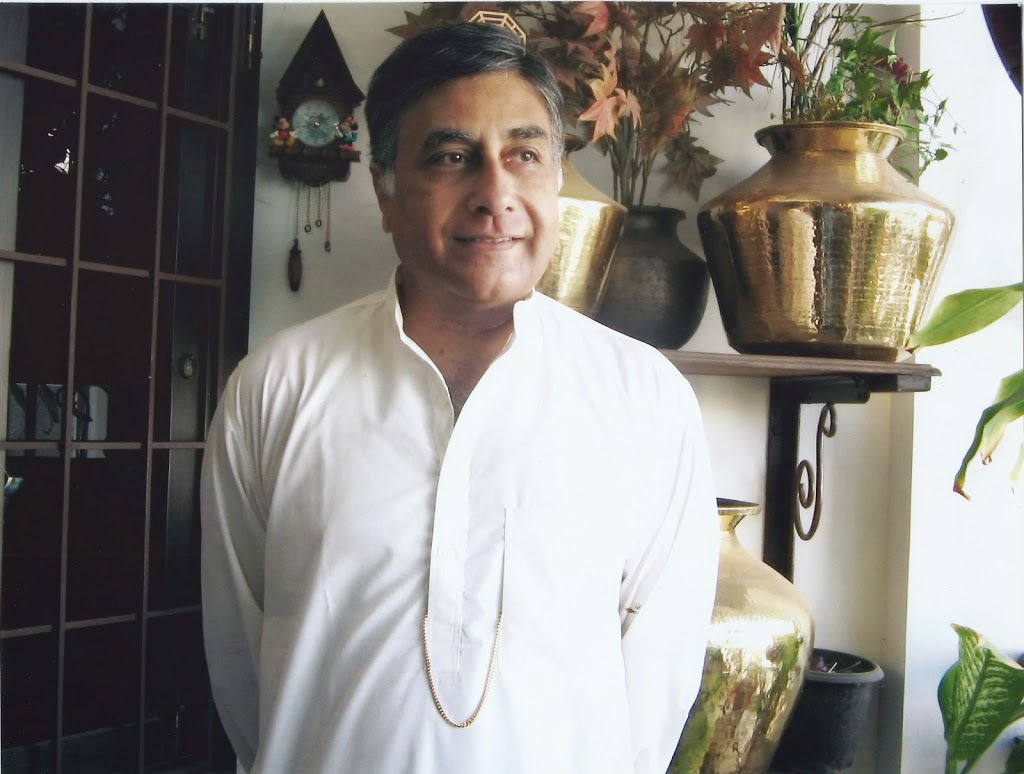

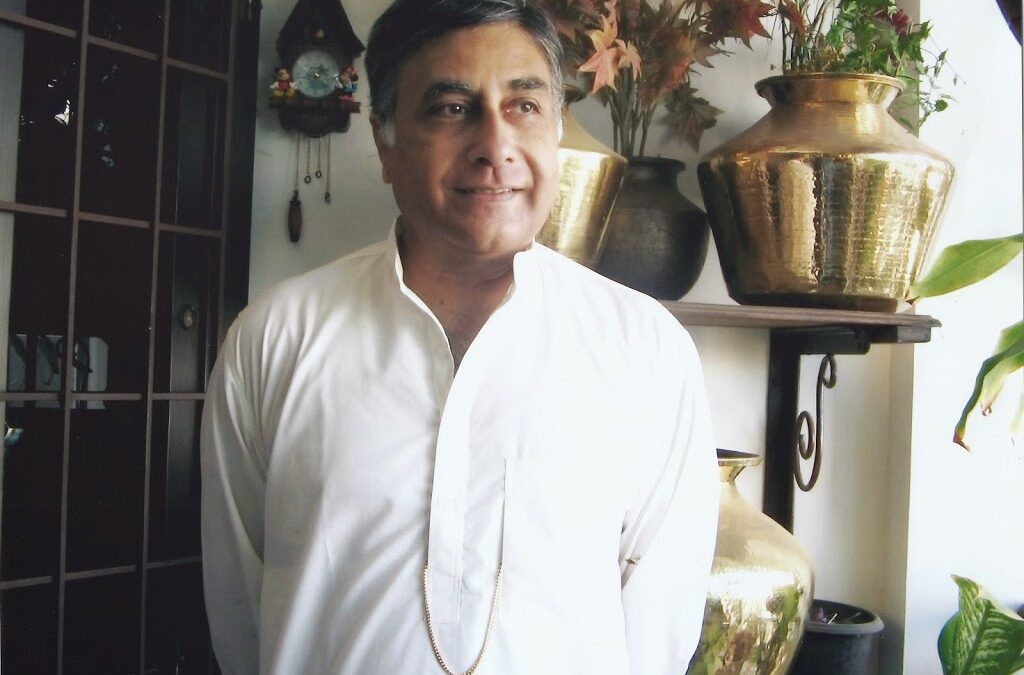

Centre Stage – P.C. Ramakrishna

P.C. Ramakrishna, veteran theatre actor and director, recounts to Saritha Rao Rayachoti some of the high points of his 50-year association with English Theatre.

If performing Carnatic music professionally had been more remunerative, P.C. Ramakrishna would perhaps be better known today for his prowess on the Mridangam. In the 1960s, faced with the choice of continuing to play the instrument or taking the first steps towards a corporate career, Ramakrishna chose the latter. However, what has remained unchanged over the last 50 years is his commitment to his true calling – theatre.

Ramakrishna is part of The Madras Players, the oldest running English theatre group in India, that itself turns 60 in 2015. This span of time, we realise, parallels perhaps the very growth of English Theatre in the country.

“Initially, The Madras Players produced plays written by English, American, Russian and European writers.” recounts Ramakrishna, “But since the 1970s, four Indian playwrights emerged, who changed forever, the metier – Badal Sircar, Mohan Rakesh, Vijay Tendulkar and Girish Karnad. We enacted their plays translated to English back then, but today many of our plays are written in English, including from Chennai, writers like Sabita Radhakrishna, Chetan Shan, Timeri Murari and Shreekumar Varma.”

Ramakrishna has been an integral part of productions such as Land of the Free, Silence! The Court is in Session, Rural Phantasy (based on Kalki’s Kanayazhiyin Kanavu), Meghadootam, Dance Like A Man, Mangalam and more recently, Honour, which he directed. He has played innumerable characters, from the titular role in his first play, The Amazing Mr. Scuttleboom to his most recent enactment of Mr. Whymper in the Peter Hall adaptation of Animal Farm.

“In 1960 we had 50 to 60 people in the audience for English plays with Indian themes. Today we have 3 shows running at full house. The audience’s expectations of a theatre experience have also grown. Take for instance, our production of Mike Cullen’s Anna Weiss in 2000.”

The play on the subject of False Memory Syndrome is about a therapist whose young patient, in the midst of therapy, remembers being sexually molested by her father.

Ramakrishna recalls, “The subject was very intense. We rehearsed on camera because the actors playing the two women were not comfortable with onlookers. I found it traumatic to work on this play and return home to two teenage daughters. At the end of the performance, the audience stayed in their seats for almost 20 minutes, reluctant to leave without an interaction on the subject. The therapist, Dr. Vijay Nagaswami, who was part of the audience, spent some time answering the audience’s questions.”

Sivasankari’s Karunai Kolai was conceived as an English play by Ramakrishna and rendered an ending different from the original with the author’s permission. “Mercy is a monologue I directed in 2005, about a couple who are very devoted to each other. The play features the predicament of the husband, as his wife shows no signs of recovering from coma following a mishap. I remember the audience opinion being clearly divided on the ending. The men predominantly agreed with the husband’s point of view, empathising with the guilt of the caregiver. But the women in the audience believed that the ending was not fair to the character of the wife.”

He holds up ‘Water’ as an example of the writer’s keen observation of a social situation. “Komal Swaminathan’s Tamil play, Thanneer Thanneer moved me immensely when I first saw it. In 2012, we approached his daughter about producing it in English at coincidentally the same time that the idea occurred to her. The brilliance of Water is that the social situation and corruption depicted in it are as true of today as they were when the play was first enacted in the Tamil original 32 years ago.”

Ramakrishna retired from a corporate career in 1993 in order to devote more time to theatre. That year, he also dabbled briefly in Tamil cinema, with roles in movies like May Maadham and Mani Rathnam’s Thiruda Thiruda. With his accent-neutral diction and resonating voice, he is also a much sought after voice-over professional for corporate films and documentaries for clients such as BHEL and ISRO, with the latter’s videos about their launch vehicles and satellites carrying his distinctive voice.

Ramakrishna speaks of mike-friendliness, and the distinction between a singing voice and a speaking voice, which brings us to the care he takes to keep his vice sounding the way it does. “It works for me, but may not work for a singer. Speaking requires short breaths and singers take long breaths – the discipline is different. I am blessed with the DNA, but I do take care of my voice with some rudimentary breathing exercises. I drink liquids at room temperature and avoid spicy foods. I do not speak above the ambient noise level, at, say, a wedding. I also stay silent when I can.”

The last statement catches us unawares.

Ramakrishna elaborates, “Silence is an active state, and it is not at all about shutting off. An hour of silence a day leaves the voice refreshed and the mind, unclogged. This was, perhaps why the rishis of yore undertook mauna vratham. Silence is indeed the greatest rejuvenator.”

(An edited version of this article was published in the January 2015 Issue of Harmony – Celebrate Age)

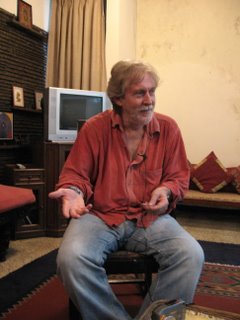

Dr. Devdutt Pattanaik

“I have a fascination for liminal beings – creatures who stand on the threshold. Like Ganesha (half elephant – half human). Or Narasimha (the man-lion incarnation of Vishnu). Or Janus (two heads facing two directions). Or the shape-shifting Budh/Mercury. ” says Dr. Devdutt Pattanaik.

Dr. Pattanaik himself stands at the cusp of many simultaneous existences. He is a medical doctor by qualification, a mythologist by choice and Chief Belief Officer by designation, aligning beliefs within Future Group. That is, when he isn’t writing one more book, speaking at one more convention or rendering one more illustration.

“I had a general understanding of mythology like anybody else but this emerged organically over time, post my medicine. I wasn’t sure I wanted to practise medicine. I was getting into a day-job in the pharma industry that I didn’t quite enjoy. Mythology became my comfort zone and it led to this wonderful world that I entered.”says Dr. Pattanaik.

Dr. Pattanaik is the author of over ten books on Hindu mythology with subjects ranging from Shiva to Hanuman to Vishnu to Devi. He has created a handbook of Hindu mythology called ‘Myth=Mithya’ and more recently, ‘Seven Secrets from Hindu Calendar Art’ and ‘The Book of Ram’. His book, ‘The Pregnant King’ is fiction written in the style of mythology. The books usually also contain his illustrations – graceful pen and ink renderings that capture the essence of accompanying myths.

Surprisingly there is no book as yet on Krishna, by far one of the most adored of Hindu gods. Dr. Pattanaik says, “Krishna is a major part of all my books, particularly on Vishnu. But a book purely on Krishna is one I want to write desperately. It was to be published but somehow did not happen. It has always run into trouble. I am very superstitious – maybe I have not understood it correctly. At the right time, it will happen.”

Dr. Pattanaik believes that Krishna Charitra (The Krishna Ethos) requires a certain level of maturity. “People like the little baby Krishna but Krishna Charitra is right from Krishna’s birth to death. It is difficult also because there are different pockets of knowledge. For example, North India is not aware that in South India, Radha is not worshipped. Until you point it out, South Indian devotees actually don’t realise that there’s no sign of Radha in their temple.”

Speaking about mythology as the subjective truth of a people, Dr. Pattanaik says, “Mythology is what you think about yourself and your understanding of life. This subjective truth is communicated from generation to generation through stories, symbols and rituals. So when I read the Ramayan and Mahabharat, I get access to the soul of India, to the subjective truth of our ancestors. If I want to study American culture, I have to study the mythology of America – American stories, symbols and rituals – that contain the subjective truth of America. Like ‘All humans are born equal’, ‘If you work hard, you will be successful’, ‘The American Dream’ and the Statue of Liberty.”

As an example of ritual, Dr. Pattanaik talks about the worship of Ganesha. “Imagine every year you bring a clay idol to your house and worship it. After 10 days, you dissolve it in water. Imagine doing this every year, year after year, generation after generation. Why don’t you buy a plastic idol or a permanent statue? Why the ritual involving ‘avahan’ (getting the idol home) and ‘visarjan’ (getting rid of it)?What are you telling the child? That nothing is permanent. But it is subliminally communicated from ancestors to the next generation. It seeps into your subconscious and you don’t even realize it.”

Dr. Pattanaik laments that over time, people have given so much importance to stories that the thought behind the stories are forgotten. “We also get edited versions of stories and authors put in their own thoughts and feelings. So you don’t realise the subjective truth that is being communicated.” he says.

On the subject of similarities and differences between mythologies, Dr. Pattanaik says that similarities reveal that we’re human ultimately, but dissimilarities will show what is culturally different. “So, the commonalities try to explain life and make sense of life and the differences are about how they approach it. For example, Western stories are obsessed with the Hero Myth. Greek mythology has stories of people who do some extraordinary action even when opposed by the gods. Biblical mythology constantly shows stories of people who surrender to the will of God. Whereas the dominant theme in Indian mythology, particularly Hindu mythology is the futility of trying to control your life, to step back and reflect on it. Each mythology is trying to explain life.”

Dr. Pattanaik explains about the common themes that run across cultures. “There are stories of death and resurrection (resurrection as different from rebirth) that are a recurring phenomenon in most parts of the world, like the stories of Adonis, Kamadeva, Ishtar and Dumuzi. The story of a great apocalyptic climax is common. But in India, after the climax, life starts again, which is not there in the western traditions. The great saviour who will save you from problems is always there. There is the mother goddess – fertile, loving and charming – all over the world. Across the world, the feminine form is seen in a more emotional way while the masculine form is seen in a more aggressive way. Everybody has gods and demons, everybody has heroes and villains.”

Among the myths he has studied and written about, and the liminal beings he is fascinated by, Dr. Pattanaik is particularly drawn to the centaur. “I like the idea of the teacher who is alone, students come to him and he teaches them. Then they move on and discover themselves. But the centaur stands atop a hill, a threshold god. He is animal as well as human. He is wise as well as wild. He is a loner but at the same time, he teaches people to be developers of society.”

(An edited version appeared in Culturama’s April 2010 Issue. Pic courtesy Dr. Devdutt Pattanaik)

Also read a review of Devdutt Pattanaik’s Jaya – An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharat here.

Shekar Dattatri – All Things Wild and Wonderful

However, this much is evident – meeting Shekar is like being swept away in a deluge of anecdotes and sound-bytes. He speaks of his early introduction to the wild when his sister gifted him a book by Gerald Durrell and his discovery that one doesn’t have to go into the jungles to watch animals, the ones in the backyard were just as interesting. At age 13, he remembers cockily asking Rom Whitaker if he could join the Madras Snake Park as a volunteer as he already knew how to handle snakes. Rom agreed with the usual word of caution, and Shekar began to spend his weekends there, gradually progressing to accompanying snake-catching Irula tribals on trips. When he attended school during the week, he sat in the last bench, immersed in books on wildlife.

One audience that Shekar would like to focus on, is children – “Children are like sponges – they soak up so much information and are yet to become cynical. Given the right information, they’ll grow up to be a generation that’s much more proactive and conscious of these issues. As part of the Rolex Award, one of my objectives is to build a body of work with short films on different issues which could help equip school libraries, and be played during environmental science classes.”, he says.

Which brings us to the general impression of wildlife filmmaking being a very macho vocation, with images of striking cobras and attacking leopards coming to mind. “Yes, there’s adventure around every corner, but if you ask me, I feel much safer amidst wildlife in a jungle – it’s cities and people that I’m wary of!” he says.

Sanjna Kapoor

In the happy jumble that’s her office, amidst telephone calls, cash vouchers and work on the website, Sanjna Kapoor got talking about Prithvi Theatre. She was between two theatre festivals – The Prithvi Theatre Festival in Mumbai has just ended the day before and she leaves for Delhi where she’s organizing the festival there.

Sanjna is part of the Kapoor family, considered by many as the first family of Indian cinema with actors such as Prithviraj Kapoor, his sons Raj Kapoor, Shammi Kapoor and Shashi Kapoor (Sanjna’s father) and their children.

Sanjna’s grandfather, Prithviraj Kapoor started Prithvi as a theatre group. When the touring theatre company of the Kendals, Shakespearana came to India, Prithviraj Kapoor’s son, Shashi Kapoor met, fell in love with and married the Kendals’ daughter, Jennifer. Herself an accomplished stage actress, Jennifer was to spearhead Prithvi Theatre’s revival as a venue when Prithviraj Kapoor passed away. Sanjna was five at that time.

The Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai was instituted to nurture the development of theatre in India. It is primarily a theatre venue, but goes beyond the function of a mere venue by supporting projects aimed at growth of theatre in India. Currently, Prithvi hosts over 400 performances a year by over 50 theatre groups. It boasts an average audience of 80% of capacity, which is approximately 65000 people per year. Since 1993, the organization has been involved in developing alternate performance venues with the objective of taking theatre to the audience.

Sanjna has memories of having class picnics at the theatre, and playing ‘chor-police’ (cops & robbers). “At the age of nine, I was running around barefoot with my Lhasa Apso in the plot where the Prithvi Theatre as we know it now, was being constructed. I remember looking at the architectural plans and seeing it all come together like a jigsaw puzzle. I was on the periphery of the actual building of the theatre.” She says.

Later, when the venue opened its doors to theatre groups, she remembers going for late night shows with her parents and falling asleep on the seats at the back, surrounded by the reassuring sounds of a play in production.

In the first festival in 1983, Sanjna was fifteen and actively participated as a volunteer and recounts it as a fantastic experience. Sanjna went on to act in a few Hindi movies, has been involved in the creation of two books, one on the Ranthambore National Park and the other on Masai Mara in Kenya. She has also helped compile the photographs for her father’s book, Prithviwallahs, published in 2004, co-authored with Deepa Gehlot.

While she’s been involved with Prithvi for a long time, she officially came on board as a Director of the organization in 1990.

She counts as her inspiration, her maternal grandfather, Geoffrey Kendal, who had his own theatre company. She recounts, “He was clearly my inspiration, he was my hero. He traveled around the country, and told me stories of his experiences. He had the ability to make the most mundane hamburger sound like the most exotic meal. It’s these stories that completely whetted my appetite for wanting to be part of theatre, sadly, wanting to be part of a traveling theatre company. I say sadly because it doesn’t really exist in reality. My dream was always to have a bus filled with actors and props and costumes, drive around the country and perform wherever we can. That may not be possible just for the economics of things.”

Sanjna now lives in Delhi and visits Mumbai to manage the theatre, spending more time whenever there’s a big event like the Prithvi Theatre Festival to organize.

In the happy jumble that’s her office, amidst telephone calls, cash vouchers and work on the website, Sanjna Kapoor got talking about Prithvi Theatre. She was between two theatre festivals – The Prithvi Theatre Festival in Mumbai has just ended the day before and she leaves for Delhi where she’s organizing the festival there.

Sanjna is part of the Kapoor family, considered by many as the first family of Indian cinema with actors such as Prithviraj Kapoor, his sons Raj Kapoor, Shammi Kapoor and Shashi Kapoor (Sanjna’s father) and their children.

Sanjna’s grandfather, Prithviraj Kapoor started Prithvi as a theatre group. When the touring theatre company of the Kendals, Shakespearana came to India, Prithviraj Kapoor’s son, Shashi Kapoor met, fell in love with and married the Kendals’ daughter, Jennifer. Herself an accomplished stage actress, Jennifer was to spearhead Prithvi Theatre’s revival as a venue when Prithviraj Kapoor passed away. Sanjna was five at that time.

The Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai was instituted to nurture the development of theatre in India. It is primarily a theatre venue, but goes beyond the function of a mere venue by supporting projects aimed at growth of theatre in India. Currently, Prithvi hosts over 400 performances a year by over 50 theatre groups. It boasts an average audience of 80% of capacity, which is approximately 65000 people per year. Since 1993, the organization has been involved in developing alternate performance venues with the objective of taking theatre to the audience.

Sanjna has memories of having class picnics at the theatre, and playing ‘chor-police’ (cops & robbers). “At the age of nine, I was running around barefoot with my Lhasa Apso in the plot where the Prithvi Theatre as we know it now, was being constructed. I remember looking at the architectural plans and seeing it all come together like a jigsaw puzzle. I was on the periphery of the actual building of the theatre.” She says.

Later, when the venue opened its doors to theatre groups, she remembers going for late night shows with her parents and falling asleep on the seats at the back, surrounded by the reassuring sounds of a play in production.

In the first festival in 1983, Sanjna was fifteen and actively participated as a volunteer and recounts it as a fantastic experience. Sanjna went on to act in a few Hindi movies, has been involved in the creation of two books, one on the Ranthambore National Park and the other on Masai Mara in Kenya. She has also helped compile the photographs for her father’s book, Prithviwallahs, published in 2004, co-authored with Deepa Gehlot.

While she’s been involved with Prithvi for a long time, she officially came on board as a Director of the organization in 1990.

She counts as her inspiration, her maternal grandfather, Geoffrey Kendal, who had his own theatre company. She recounts, “He was clearly my inspiration, he was my hero. He traveled around the country, and told me stories of his experiences. He had the ability to make the most mundane hamburger sound like the most exotic meal. It’s these stories that completely whetted my appetite for wanting to be part of theatre, sadly, wanting to be part of a traveling theatre company. I say sadly because it doesn’t really exist in reality. My dream was always to have a bus filled with actors and props and costumes, drive around the country and perform wherever we can. That may not be possible just for the economics of things.”

Sanjna now lives in Delhi and visits Mumbai to manage the theatre, spending more time whenever there’s a big event like the Prithvi Theatre Festival to organize.

The Many Faces of Tom Alter

Perhaps the best known face of the angrez (Englishman) in the hindi film industry, Tom was born in India at Mussoorie and went on to ultimately do a course at Pune’s FTII (Film and Television Institute of India).

His first role in a feature film was in Charas (1976) and his latest, is in Alag (2006). Tom looks for a certain something in the characters he plays for the sake of the role. “If the role is meaty, I like to see some change, some colours in the personality. I like to see growth and change in the character. If I see that in the script, then I get very excited about the role, whether it has negative shade or positive ones.”he says.

Tom has not only done Hindi movies, but also many regional films, including three Malayalam Movies ( I.V.Sasi’s 1921, Priyadarshan’s Kaala Pani and a film called Oru Thooval Pakshikal). Besides these, he has done two Bengali and one Kannada Movie, the latter was M.S. Sathyu’s Kanneshwara Rama where he co-starred with Anant Nag, Shabana Azmi and Amol Palekar.

More recently, Tom has been part of two exciting theatre projects, an Urdu solo on Maulana Azad and the other, ‘Mahatma and the Poetess’ on the letters between Mahatma Gandhi and Sarojini Naidu.

Not many people know that Tom has also written three books. The first, a book on cricket called The Best In the World, was co-authored by Ayaz Memon. His other two books are novels, Rerun at Rialto and The Longest Race, both set in his hometown, Mussoorie. “I want people to read with the same passion with which I write. I wrote ‘The Longest Race’ in a particular way, it is very critical of the athletic system.” He says

Which brings us to his passion for sports, especially cricket that he also plays. He has also written extensively for Sportsweek. As a sports enthusiast, he has been credited with organising the first national triathlon in the 1990s with swimmer Anita Sood and swimming coach, the late Sandeep Divgikar.

“While my publisher has asked me to write another novel, what I really want to write about is change.”, he says, “It’s a strong thread that runs through my books. More importantly, I’m questioning if so much change is really necessary. Things are changing, but are they improving? The more the changes, the faster the spiral. ” he says.

(an edited version published in the November 2006 issue of At A Glance. Photograph by author.)