Can the world of books be a little too cut off from the rest of the world we live in?

Partiban’s Dream – Kalki Krishnamurthy – Translated by Nirupama Raghavan

Sixteen-year-old Nirupama Raghavam’s tryst with Kalki Krishnamurthy’s Parthiban Kanavu goes back to the time, three years ago, when her grandmother gifted her a few Tamil books hoping to get her to learn the language.

“Most of the books my grandmother gave me were non-fiction. But Parthiban Kanavu stood out because, quite literally, the book had an interesting cover and was also one of the few Tamil fiction titles among the lot,” says Nirupama of the book that proved a turning point for more than just her reading habit.

Last year, Nirupama completed her translation of Parthiban Kanavu from its Tamil original to English. Her recently relased book, published by Tulika Books in association with the MR AR Educational Society is called Parthiban’s Dream. And to think this dream grew out of Nirupama’s need to express the story to someone who didn’t read Tamil.

“One of the students in the non-profit school that my mother runs, didn’t read Tamil but wanted to know what the book was like. I narrated the story with such detail that my mother insisted I should write it down as a translation. And look how far that has come!” she says, visibly excited to see her work in print.

“I spent ten months translating the book, although I was reluctant at first. After getting help for the first seven chapters, I started translating it on my own. In retrospect, it has been a great experience, as my interest didn’t slacken and boredom didn’t creep in. It probably has to do with the fact that the original book itself is so exciting,” she exults.

“I fell in love with the characters in Parthiban Kanavu – Chakravarthi, the emperor, so majestic, yet so free of ego. Imagine a ruler wielding so much power, yet not letting it affect him! And of course – Valli, an extremely smart woman. Although women in that era have been portrayed as powerless, here’s one who is represented as extremely intelligent. Also, the original was written so well, that it has inspired me to learn more about South Indian History.”

Nirupama lives in Arasavanankadu, a village near Tiruvarur where her mother runs a non-profit school.A n interesting factor in Nirupama’s upbringing is that she has been completely home-schooled.

Doesn’t she miss attending a regular school? “ I don’t miss company as we have the school my mother runs. And add to that the fact that I am taught for about two hours every day leaving me free to learn anything I want the rest of the day! Besides, I also get to teach Maths, Geography, chanting and a little music part-time at the school.”

Moreover, books form an integral part of Nirupama’s life. Isaac Asimov, Terry Goodkind, Ayn Rand and Richard Bach are among her favourite authors. K.M. Munshi’s Krishnavatara and Rajaji’s Mahabharata have also played a part in developing her taste in books.

So, where to from here, young Nirupama? “I currently write for myself and am in the process of writing something original which should be completed by December this year. As for the future, I am yet to decide what I want to do. It’s still “Work in Progress/Under Construction.”

Nirupama Raghavan’s book, Parthiban’s Dream is available in bookstores in the city.

(edited version published on November 18, 2004 in Madras Plus, the city features supplement of The Economic Times, Chennai. Pic as published in Madras Plus)

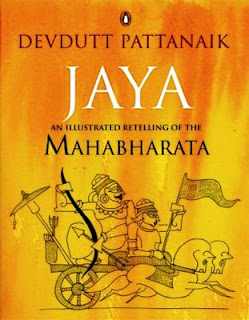

Jaya – An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata

The Mahabharata by Veda Vyasa is a sprawling epic that has spawned many an interpretation and philosophical debate. It is centered on the concept of Dharma – interpreted variously as ethic, duty, the path of righteousness and the natural law.

At the heart of the story is the futile rivalry between the Pandavas and their cousins, the Kauravas, that leads to a great war which the Pandavas win. It begins with the recounting of the ancestry of the two warring factions and ends with Yudhishtira, the eldest Pandava ascending to heaven, only to find his arch rival Duryodhana already there.

Devdutt Pattanaik, a renowned name in the field of Indian Mythology, takes on the onus of demystifying the grand epic, delving into its intricate plots and sub-plots. Pattanaik titles his book Jaya – the original name of the epic that we now know as Mahabharata. He narrates the story succinctly and dwells on the fascinating interconnectedness of events and characters, the layers, paradoxes and symbolisms. Pattanaik’s enthusiasm is infectious – he includes folklore, interpretations and cross-references in other texts – and his accompanying illustrations are exquisite.

The pivotal chapter on the game of dice, for instance, begins with the envious Duryodhana returning from Yudhishtira’s coronation. His uncle, Shakuni devises a plot to overthrow the Pandavas with loaded dice. We see the heady lure of a gamble that dulls Yudhishtira’s intellect enough to pawn away his wealth, his kingdom, his brothers and finally, Draupadi, their wife. When Draupadi is publicly disrobed by the Kauravas, Dhritharashtra, the father of the Kauravas intervenes and offers her boons by which she frees her husbands. Sadly, Yudhishtira squanders away this too and the Pandavas are exiled for 13 years. In the footnotes of this chapter, we learn that Draupadi is worshipped in parts of India as a goddess and there are rituals enacted by men representing the Pandavas, seeking her forgiveness.

While Pattanaik’s Jaya loosely follows the chronology of the original epic, the author invests time in dwelling on significances. There are stories within stories, curses and blessings that change destinies, and repercussions across timelines and beyond lifetimes. In this retelling, Pattanaik chooses to reiterate that the theme of the Mahabharata is conveyed in the character arc of Yudhishtira who first chases Vijaya (victory over others) but finally realises Jaya (mastery over self).

An edited version appeared in Culturama’s April 2011 Issue.

Also read an interview with Devdutt Pattanaik here.

The Silent Raga – Ameen Merchant

It is the 1980s in Sripuram, Tamizh Nadu. When Janaki, talented in playing the Veena, walks away from her overbearing father and maternal aunt, she leaves behind not only a hard-earned, spotless Brahminical reputation but also her beloved younger sister, Mallika.

Ten years later, Janaki, now Janaki Asgar lives in Mumbai. She receives an unsigned but hardly anonymous letter from her maternal aunt informing her of her father’s failing mental faculties and Mallika’s financial struggles. Janaki writes to Mallika requesting to meet her in Chennai.

Both letters stir strong emotions for the sisters as each sister braces herself to meet the other. It is through their eyes and alternating narratives, that we piece together the story of their childhood.

We meet the mother, dead but still a silent observer in the form of a garlanded portrait. We meet the bank manager father, Venkatakrishnan, a man who is melodramatic even in his silences. He lives life on his terms, but ensures his daughters are brought up traditionally. Then there are Janaki’s friends, Kamala and Revathi, who are as different socially as they are in temparament, but unanimous in their love for music and unconditional affection for Janaki.

We also meet Gayatri, the girls’ widowed maternal aunt, who exerts authority over the goings-on in the household. Through Janaki’s eyes, we come to realise the motives behind Gayatri’s visits. Through Mallika’s younger eyes, we see Janaki’s gradual assertion of independence. When Janaki leaves Sripuram, we also sense Mallika’s fear of having her own wings clipped.

When the sisters finally meet ten years later it is not the misgivings of the past that take centre stage, but the strong bond they share despite a difficult childhood in a dysfunctional family.

Silent Raga captures the social intricacies of Tamizh Brahmin life in an Agraharam (traditional living quarters for the Brahmin community serving the local temple) in small-town Tamizh Nadu. It conveys the conservatism, the thrift, the social mores imposed on young girls of marriageable age as well as the paradoxes that are not spoken about.

The vocabulary is authentic, the detailing is intricate and the protagonists are so well nuanced, that this evocative debut novel reads like a translation from the Tamizh language.

Nominated for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize in 2008 in the best first book category.

(An edited version appeared in Culturama’s February 2011 Issue)

Johnny Gone Down – Karan Bajaj

Price – Rs. 99

Over twenty years and 324 taut pages, Nick Arya goes from being a young MIT graduate with a promising NASA career in hand, to a player in a game of chance unhesitant to put a gun to his own head.

Nick’s journey begins on the day of his graduation when, on a whim, his friend Sameer picks Cambodia as a holiday destination little knowing that the country was at that very moment, being taken over by the Khmer Rouge. Nick helps Sameer escape, but he himself is captured. When he does escape Phnom Penh, it is into a life that reboots itself every few years with a different alias in a new location.

Nick discovers a quiet resilience that becomes invaluable in the years to come as he loses an arm to gangrene, falls in love, becomes a Buddhist monk, becomes an accountant to a drug empire, fathers a child and loses everything many times over.

Nick’s character arc is intertwined with those of many others – Dechen the Buddhist monk in Thailand, Lara the supermodel from Brazil, Marco the druglord, Philip North a struggling entrepreneur in Minnesota and Dayaram, his opponent in the game of death in India – and Nick is transformed by these intertwinings even as he radically changes their lives in the brief period he knows them.

At every step, the book challenges the reader’s tendency to stereotype people, places and situations, but most of all, the mindset of a Non Resident Indian protagonist. Nick has an all-encompassing world view, yet, he also draws into his life the very events that break and make him over and over again. Nick makes sacrifices but is human enough to acknowledge the regret of having made them. He steadfastly refuses to own anything and is most content owning only the clothes on his person as he charts his rocky destiny through Cambodia, Thailand, Brazil, USA and finally, India.

An edited version appeared in Culturama’s September 2010 Issue