Vibrant Threads – Paithani

In the western Indian state of Maharashtra, a traditional Paithani saree is regarded as a family heirloom, passed down to the daughter or the daughter-in-law. Some families have 100-year old Paithanis, lovingly preserved over the generations. It was called ‘maha-vastra’ (grand attire), part of trousseaus and worn on special occasions like religious ceremonies and weddings.

The Paithani saree is named after the place it originated from – Paithan, situated about 40 kilometres from Aurangabad. However, these days, they are woven predominantly in a place called Yeola, near Nasik.

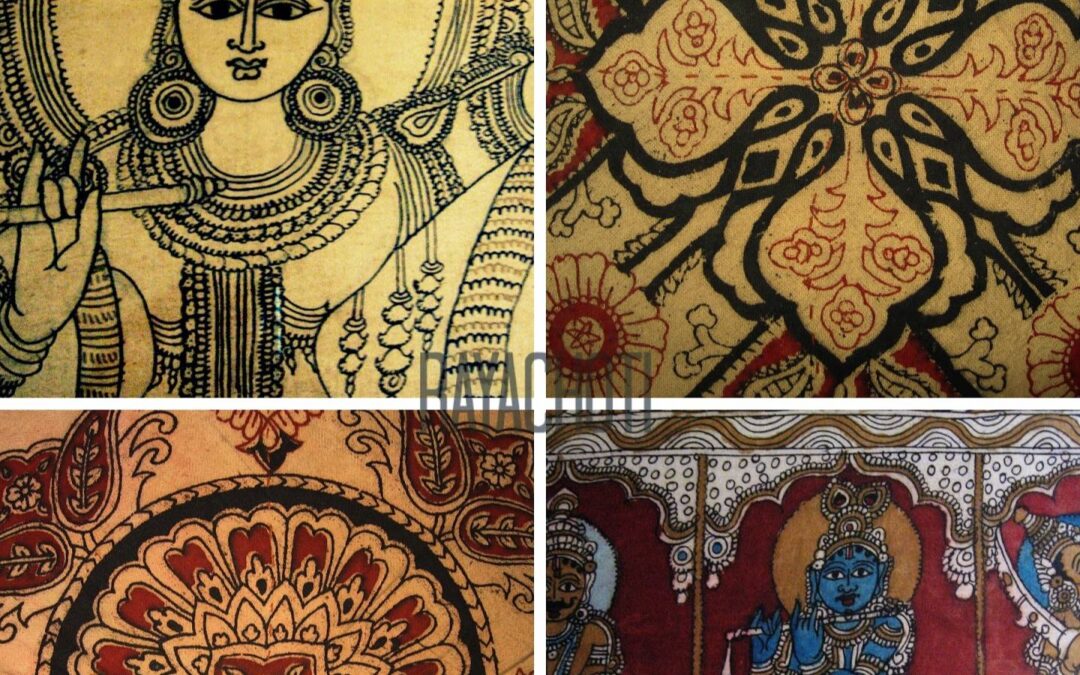

A combination of criss-crossing border design along with colourful motifs on the ‘padhar’ (end-piece) make a typical Paithani. While the border threadwork in traditional Paithani was woven in gold thread (zari), subsequently, silver thread with a gold finish began to be used. The end-piece of traditional Paithani sarees are woven with gold thread in its warp thereby making a shimmery base for the colourful motifs to be worked into the weft.

The motifs are borrowed from nature. There are ‘munia’ (parrots), ‘bangdi mor’ (peacock inside a ring), ‘asavali’ (creepers), ‘kamal’ (lotus) and ‘narali’ (coconut). These are worked in gold thread when placed in the body of the saree and in colour when on the end-piece.

The richness of a Paithani also comes from ‘buttis’ (small gold motifs) that dot the vibrant colours in the body of the saree. The silk saree body is usually in colours like magenta, peacock blue, turmeric yellow and crimson. Dual-shaded sarees, called ‘dhup-chaav’ (light and shadow) are also made with different colours in the warp and weft, for example, red and green.

However, authentic Paithani is not for the common man with prices ranging from a few thousand rupees to even half a million rupees!

It is one of the saree types that comprises a traditional categorisation called ‘shalu’ or sarees in muslin with gold threadwork, made exclusively for the royalty and aristocracy.

One reason for the exclusivity (and the price) of a Paithani could be the use of gold thread. The other reason being the workmanship involved in weaving the coloured motifs on to the base of the end-piece. Even today, it takes a month to handweave one simple Paithani and several months, for more intricate work.

Paithanis are usually woven in pure silk but there are some synthetic blends in non-traditional colours using gold-copper threadwork also available. However, they all carry the signature Paithani motifs and border design.

(an edited version appeared in the June 2009 Issue of At A Glance. Pics by author)